exhibition

The will to influence is at the core of any exhibition.

-Bruce W. Ferguson, Exhibition Rhetorics

The Oxford English Dictionary defines exhibition as a “public display (of works of art, manufactured articles, natural productions, etc.)” and as “the place where the display is made”. As such, an exhibition exists both as event and space, performance and site.

As a noun, exhibit takes on a diminutive form in reference to exhibition. It is defined as an object “composing an exhibition”. In its verb form, to exhibit encompasses the performative aspects of exhibition. The Oxford English Dictionary offers a variety of relevant definitions: “to submit or expose to view; to show, display”, “to manifest to the senses, esp. to the sight” and “to show publicly for the purpose of amusement or instruction”. [2]

The modern day conception of the exhibition, as a display of art or artifacts for, often temporary, public viewing, originated in the eighteenth century. Before that, most artworks outside of the religious sphere were largely confined to private collections and available to only the most fortunate eyes. Martha Ward cites the Paris Salon, regularly beginning in 1737, as a watershed moment in the move towards exhibitions as a public showcase. [3] Previously, across Europe, academies and other institutions held exhibitions only for their members and society’s elite. The transition towards public exhibitions in the eighteenth century fundamentally shifted both the reception and production of art and the display and dissemination of cultural artifacts.

The exhibition is intimately concerned with collection, organization and display. As such, exhibitions have been seen as instruments of power and control. Through their assemblage they construct and amplify meanings of the objects they present and structure the experience of the spectator who views them. In “The Exhibitionary Complex,” Tony Bennett adopts Michel Foucault’s framework of power/knowledge to address the politics of power inherent to the medium of the exhibition. He writes that exhibitions “formed vehicles for inscribing and broadcasting the messages of power … throughout society.” [4] Exhibitions display “the tendency for society itself – in its constituent parts and as a whole – to be rendered as spectacle. … The ambition towards a specular dominance over a totality was even more evident in the conception of international exhibitions which, in their heyday, sought to make the whole world, past and present, metonymically available in assemblages of objects and peoples they brought together and, from their powers, to lay it before a controlling vision.” [5] The Great Exhibition of 1851 in London marked the beginning of such a trend towards achieving dominion over both knowledge and the public via exhibition [image: crystalpalace.jpg].

The exhibition was an ethnographic playground, in both its contents and performance: it consisted of over 100,000 exhibits from over 20,000 domestic and foreign exhibitors and was seen by an audience of over six million people. [6] The Great Exhibition proved to be a huge success for its organizers and, in turn, provided a model of “how a great manufacturing nation should develop and instruct – and hence create – its subjects.” [7] Following the Great Exhibition, international exhibitions, which displayed everything from the products of industry to artworks to the peoples and artifacts of distant cultures, flourished across Europe and North America for the remainder of the nineteenth century. Bjarne Stokland writes that during that time, exhibitions “grew into gigantic instruments for education and refinement, where contemporary ideas and norms were formulated and imprinted through visual communication”. [8]

While the form of the International Exhibition reached its peak at the end of the nineteenth century, the medium of the exhibition has lived on as the primary vehicle of display within the realm of the museum. The enduring impact of the exhibition as the principal mode of presentation is evident through its employment across the entire spectrum of museum types, from natural history museums to cultural museums, but its lasting impact is acutely seen within art museums and the other satellite spaces of display within the art world. Since the Paris Salons, the exhibition has taken center stage – or, rather has become the center stage – in the dissemination and presentation of artworks. In their introduction to Thinking about Exhibition, Reesa Greenberg, Bruce W. Fergeson and Sandy Nairne declare that exhibitions “have become the medium through which most art becomes known. … Exhibitions are the primary site of exchange in the political economy of art, where significance is constructed, maintained and occasionally deconstructed. Part spectacle, part socio-historical event, part structuring device, exhibitions – especially exhibitions of contemporary art – establish and administer cultural meanings of art.” [9]

As a structure of presentation, the mere concept of an exhibition carries enormous weight and authority. Given the context, it can be enough to label an event or space an exhibition and thus declare, by default, the contents therein works of art. The mere action of exhibiting can transform any object into art. Art historian Svetlana Alpers has termed this phenomenon the “museum effect”. [10]

As the exhibition became rooted as the standard medium of display in the art world, artists began to investigate and problematize the medium of the exhibition itself. Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades were the first works to substantially address exhibition as a medium. His famous 1917 piece, Fountain, a re-purposed urinal displayed upside down and signed R. Mutt, radically confronted and questioned what art is and what conditions make an object art.

In calling attention to the exhibition itself, Duchamp and other Dada and Surrealist artists revealed and spotlighted a medium that prefers to remain transparent. Both Dadaism and Surrealism pursued the exhibition and the act thereof as mediums, tweaking and upsetting prior conventions to reveal the medium that encased what were previous through to be the primary media on display: the individual works of art. In their exhibitions, Surrealists “abandoned any attempt at neutrality of presentation in favor of a subjective environment that itself embodied a statement.” [11] The Surrealist approach accentuated and consumed exhibition spaces by adhering to its two main tenets: the marvelous and disturbance. Surrealists sought to reorient the spectators’ senses by subverting their expectations. For example, at the 1938 Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme at the Galerie de Beaux-Arts in Paris, visitors were greeted by the first work before they even set foot inside the gallery. In the courtyard, Salvador Dalí installed a black cab “bedecked outside with ivy, the headlights full on, glaring with brilliant uselessness into the light of day. In the back seat a scantily clad female figure with a few pet snails crawling over her. Besides her is a sewing machine, and on the floor a mass of Pampas grass and other vegetation,” all hydrated by the constant rainfall emanating from pipes lining the ceiling. [12] Once inside, the spectators were greeted by a hallway of sixteen mannequins, each outlandishly outfitted and modified by a different artist. From there, visitors entered the main gallery, a cavernous, dimly lit hall filled with four beds and a variety of works in various media hung in all different manners. The most arresting of which, and the piece that consumed and transformed the entire space, was Duchamp’s 1200 Coal Sacks, a “dropped ceiling of burlap bags, hanging just above the spectator’s heads.” [13] Through such outlandish and fantastic displays and interactions with the art space, the Surrealists acknowledged and emphasized the exhibition as a medium and the effects that various modes of display and arrangement had on the reception of the art by the spectator and vice versa.

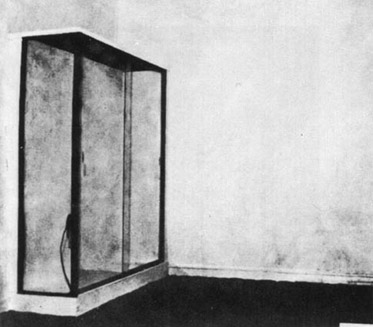

While Surrealists tended to increase a spectator’s awareness of the exhibition’s arrangement and physical space by veering towards the outlandish and the phantasmal, minimalists and conceptualists took the opposite route to ask similar questions of the medium of the exhibition. In 1958, the revolutionary artist Yves Klein mounted an exhibition at the Galerie Iris Clert in Paris entitled Le Vide (The Void). Klein removed all of the furniture from the gallery and painted the interior completely white.

By exhibiting an exhibition, Klein called attention to the often intangible structuring medium of the exhibition and its ideological effects on a physical space.

By mid-twentieth century, artists were abandoning the gallery and museum space altogether to explore the boundaries of exhibition and the power of the act of exhibiting itself. Land Art and Performance Art removed the art piece from the traditional, confining realm of the gallery space in favor of site-specific, often short-lived exhibits. Yet, artists working in such modes frequently documented their pieces or performances for posterity. In turn, these scattered remnants or renderings of the piece are what commonly allowed the work to reach its largest audience and often came to be displayed within a traditional exhibition space in place of the actual work.

The medium of the exhibition, like all media, both commands and is commanded by a host of other media: exhibition space architecture, explanatory wall labels, lighting, wall color, exhibition catalogues, and – of course – the art or artifacts themselves. As such, exhibitions form a “strategic system of representations" that mold the cultural meanings and receptions of the artworks and objects they display. [14] The exhibition’s privileged position at the center of the art world for the past couple of centuries and currently within the contemporary art scene grants it enormous weight as a medium. The exhibition is the art world’s “main agency of communication – the body and voice from which an authoritative character emerges.” [15] It is the ultimate frame: the all-enveloping medium of the art world, the conduit through with the majority of artists’ work must pass to be considered a work of art.

Neal Curley

Winter 2007